Mourning the Loss of My Dad — and His Jeep

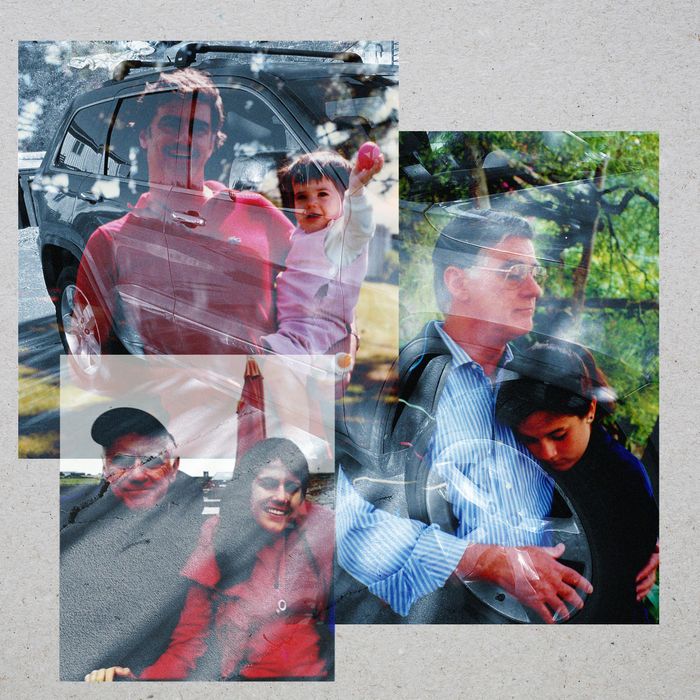

Photo-Illustration: the Cut; Photos Courtesy Katie C. Reilly

“Why does our car look so dirty?” my 5-year-old daughter, Fianna, recently asked after hopping into the back seat of our Jeep at school pickup. We watched her friend slide into a Back to the Future–looking side door of the blue Tesla in front of us before I responded, “This car is superspecial.”

We’re both right. There are deep white lines on the passenger side from scratching the car against the mailbox while trying to reverse out of our driveway. The crevices of the back pleather seats are filled with cheesy crackers, apple sauce, and pretzels. Baby wipes, small Frozen dolls, and a Baby Shark book are stuffed into the back pockets, and empty water bottles, used masks, and lollipop wrappers fill the side compartments.

But it’s not just about looks. The trunk randomly opens when the key is in your hand or pocket. The hydraulic suspension is damaged, which makes the car growl an angry hum when you drive it. The windshield wipers only work on the driver’s side, the blind-spot alarm sounds when you turn left, and inside the car, it’s always 20 degrees warmer than the daily forecast even with the air-conditioning on.

The key doesn’t lock or unlock the car. Some days, the button inside the car door won’t lock either, but it’s not really a problem, since no one has attempted to steal it yet … even though we live in an area with some of the highest motor-vehicle theft rates in the country.

“Because it’s Grandpa Jack’s?” Fianna asked as we pulled out of the school parking lot. I smiled and nodded. My dad, Grandpa Jack, died eight years ago, before I was married or had kids. I inherited his now 12-year-old green Grand Jeep Cherokee. It has kept him alive ever since.

My entire life, my dad owned Jeeps. As a kid, he drove me to school, singing oldies songs from the Del-Vikings or Fats Domino on the ride. The soft, tenor sound of his voice, how easily he carried a tune, and his gentle presence soothed me.

On the weekends, we’d drive to the Eastern Shore of Maryland. We’d stop at the Bay Bridge — halfway through our road trip from our home in Washington, D.C. — to eat Happy Meals in the “wayback” of his car with my sister and some of our friends. We always ordered a Big Mac, fries, and a Coke with too many ketchup packets. Later, he’d let me and my friends sit on the Jeep roof as he drove slowly around my parents’ farmhouse. (We did it so often that the car roof caved in.) We’d drive over mud, shorelines, and snow, bumping up and down in our seats and squealing with delight.

We spent entire weekends driving to soccer tournaments when I was in high school. Dad always packed multiple maps for different routes to the game and complained when I stretched my feet and made footprints on the front window. A mix CD I made him was usually in the car, and we’d listen to the songs together. I’d always include some oldies from the likes of Sam Cooke or the Spaniels, some father-daughter songs, and a song I thought he’d like — like Adele’s “Make You Feel My Love.” I’d explain why I chose each song, and he’d listen and hum along.

When I was old enough to drive, dad rolled his eyes at my cluelessness over how to put antifreeze in the car. Then he’d grab the key and return in an hour. “It’s winterized,” he’d say. I still haven’t learned how to do it without him.

When I’d drive home to D.C. from college in Maine in his old Jeep, which then became my car, he’d check in the day before reminding me to fill the tank and sleep, which I never did. When I attended law school at his alma mater, he invented excuses to fly in for football games and spend time together.

During my third year, my mother was diagnosed with ALS. Soon after, I moved back home to take care of her. “Thank you for everything you did,” he’d repeatedly say to me after my mother died — a year after I graduated from law school.

After her death, the two of us drank too many bottles of wine, cried on our family staircase, and went for long walks together. When it felt like the world expected me to move on from my grief — and when I still struggled with ALS-fueled nightmares and anxiety and depression from grief — he allowed me to fall apart. When others questioned why I wasn’t working or socializing more, he thanked me again and again for caring for my mom.

A year after she died, I moved away following a crush, but months later, Dad was diagnosed with cancer. My crush turned partner and I moved back to D.C. again and lived there until my father passed away four years after my mother on her birthday. After my parents died, their presence felt inescapable or, at the time, unbearable. I’d walk by the restaurant where my dad told me he no longer felt safe living home alone, because his health had deteriorated so much. Or I’d drive by the hospital where my mother took her last breath.

Months after he died, I walked alone down the aisle at my wedding. Several months later, the Jeep carried my husband, Peter, and me cross-country to California, where we now live. Here, there are few reminders of my parents, few connections to the most formative people and years in my life. Except for the Jeep.

In the first few years after we moved, the Jeep was filled with surprises. I found my dad’s small coin purse filled with quarters that he stored for tolls tucked into the armrest. His favorite Patsy Cline CD in the glove box. Multiple neatly folded maps that he used to navigate East Coast highways. I was ravaged by grief, but these little reminders of my father’s existence kept me going.

The Jeep has brought my dad into my new life without him. Peter and I drove the car to the hospital for the birth of our two daughters. Peter took the car to pick up our dog, Decoy, for the first time. Decoy, now 50 pounds, often sits in the passenger seat as I squish into the middle seat in the back with the girls. The car comes with us on family road trips along the West Coast and for quick trips to the store. When I drive over a bump or near a beach in California, the way the car jostles me brings me back.

To Fianna, Grandpa Jack is a concept, not a real person she knows. There are still many days when hearing her say his name takes my breath away, because it reminds me of his current absence. It’s then — and all the times I miss his warm hugs or the gentle tone of his voice — that the car consoles me. It’s proof on wheels that my father existed and that, for a period (however too brief), he filled my life with love.

He would have told me to sell it. There are too many good reasons to get rid of it. It’s almost $120 to fill the tank, and it’s not environmentally friendly and soon will become more expensive to own than to sell.

Every couple of months, Peter says, “I don’t think the car is going to last much longer, Katie.”

“That’s okay. We can get rid of it,” I say, trying to sound calm and casual. But he knows how much it means to me, and somehow, the car manages to chug along for a bit longer.

One recent morning, I pulled up into our driveway after dropping Fianna off at school. I bumped up and down as I drove over the broken cement that lines the entrance and desperately needs to be repaved. Then I parked, played Ben King’s “Stand By Me” loudly over the old speakers, and stayed seated in the driver’s seat.

I let every memory of my dad that the song and the Jeep conjured sit with me in the car. I wish I never had to say good-bye to my father. At least I still have time to learn how to say good-bye to a car.